Dear Will:

For as long as I can remember, my dad was a member of the Rotary Club. He went to meetings and on the occasional trip, but mostly I had no idea what it meant to be a Rotarian except for a sign that hung on the wall of his office listing the organization’s Four-Way Test. To this day every Rotary Club around the world recites it like a catechism:

Of the things we think, say or do

- Is it the TRUTH?

- Is it FAIR to all concerned?

- Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS?

- Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

You didn’t have to see that sign on his wall to know my dad was an honorable man. It showed up in everything he did and was reflected in the respect he commanded both in business and in his private life. He didn’t talk much about his affiliation with the Rotary Club, but if you knew him and later learned he was a Rotarian, you would not have been surprised.

My dad’s sense of honor showed up all the time. I remember once all nine of us had piled back into the family station wagon following dinner at a Chinese restaurant. Somehow my dad realized that he had not been charged the full amount for our meal or he had received too much change or something like that. Well, he left us all in the car and marched back into the restaurant to settle his account properly. I was amazed. We had already left. No one would ever know. But for my dad, these things mattered.

Tad R. Callister has said: “Integrity is a purity of mind and heart that knows no deception, no excuses, no rationalization, nor any coloring of the facts. It is an absolute honesty with one’s self, with God, and with our fellowman. Even if God blinked or looked the other way for a moment, it would be choosing the right—not merely because God desires it but because our character demands it.”

Throughout the ages, our most admired leaders have been men and women similarly committed to a life of virtue. George Washington famously walked away from the presidency when fawning admirers were anxious to install him as king. He chose instead (and once again) to put the interests of his country ahead of his own. (No wonder we all found it so easy to believe the apocryphal story of young George and the cherry tree.) Of Washington, Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “His integrity was pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known. . . . He was, indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good, and a great man.”

Nor should we forget that our greatest president of all, Abraham Lincoln, has always been known as Honest Abe—a remarkable honorific, especially considering how little evidence of honesty remains in political circles today. The Lincoln Heritage Museum has called Lincoln “an exemplar and a model of virtue perhaps more than any person in world history other than religious figures.”

It is in no small part due to the character of such men and women that the United States has risen to greatness from its humble beginnings. Like any nation ours has an imperfect past, of course, but if we have ever been great and ever hope to be so again, it has been and will be due to those moments when we have stood tall and done the right thing, even in difficult circumstances. When we have put the broad interests of the many ahead of the selfish interests of the few. When we have made sacrifices for humanity and given of our riches and resources to lift those less fortunate.

This is who we are—or who we were, in any case. And who we should be. So let us not be too casual nor too forgiving as we watch those now in power openly violate their solemn oaths of office; as they act to do away with those appointed to enforce ethical standards and flag conflicts of interest within the government; as they instruct others to ignore laws against bribery. As they disregard commitments, betray friendships and alliances, cozy up to the sorts of strongmen and dictators that for years we have fought to constrain and overcome. Nor should we make excuses for behavior and policies that our forebears found abhorrent and worked so hard to eliminate in the United States of America.

I’m not saying we should elect only Rotarians; but it seems obvious to me that we should not lend our support to those whose lives make it clear that they could never get in the club. In any case, before we drive away, we must all remember that there are children in the backseat watching what we do next.

PW

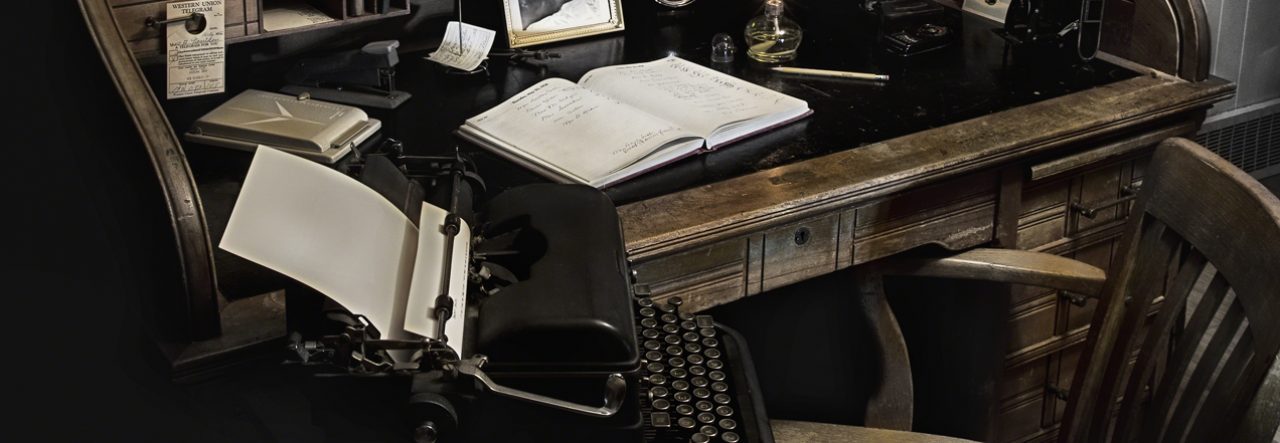

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash